FAQ: What is the Difference Between a Book Coach and a Developmental Editor?

In which I answer FAQs about book coaching.

Talk to almost any happily published writer about their editor, and you will likely hear gushing praise. Kelly Barnhill, author of the Newbery award-winning and bestselling book, The Girl Who Drank the Moon, among others, has this to say about working with her editor:

“I changed lots of things and rewrote lots of things and the story I wrote became the story it could be, and that has made all the difference.”

Barnhill is speaking here about an editor employed by her publishing house, whose job it is to make each manuscript the best it can be. Having this kind of professional pay close attention to your work is indeed one of the great pleasures of the writing life, but unless you land a publishing deal, you will not have access to it. That means that anyone self-publishing, using a hybrid publishing option, or trying to break into publishing will have to navigate the universe of editors on their own.

There are so many different kinds of editors offering different services to writers at different stages of the process that it’s hard to know what they each do and whether or not you need what they do. Knowing, however, is a skill every writer needs. I believe a lot of disappointment can be averted if writers have a better grasp of what kind of help they are looking for, which starts with being honest with themselves about their skills, their blindspots, and their goals.

To help us sort out the difference between book coaching and developmental editing, let’s start with some lines I made up. These are lines that might appear in a draft of a novel, but the same editing concepts apply to my memoir and nonfiction books:

“Hey jill do you want to hve lunch” ?

“Sorry I’m busy.

Proofreader

A good proofreader is essential to a good book. They will fix typos and grammatical errors, standardize the presentation of things such as names and numbers (often according to a “style” designed for accuracy and consistency such as AP Style or the Chicago Manual of Style), and make sure you are using the language clearly and correctly.

Even though I am introducing it first, a proofreader is usually the last person to suggest changes on a manuscript before it goes into production; they review the pages or “proofs” for mistakes and typos. When an author is responding to a proofreader’s comments, there is usually very little time or tolerance to make changes in the text. The only goal is to correct errors and clarify meaning.

Proofreading is a very particular and high-level skill. Traditional publishing houses either employ proofreaders or contract with freelancers to do the work. Writers who are self-publishing must budget for this skilled professional.

Can AI help with proofreading? Absolutely. It just reminded me to put a question mark on that last sentence. (Thanks, Grammarly!) Can it replace a human? I would say not. There are a lot of nuances to writing and a trained human can catch them.

Note that nonfiction writers need to make sure their facts are correct – the spelling of people’s names, dates, titles of books and movies, etc. Fact-checking is a different process than proofreading. Some proofreaders may be fact-checkers, and vice versa, but if you need fact-checking, you need to make sure you explicitly arrange for it.

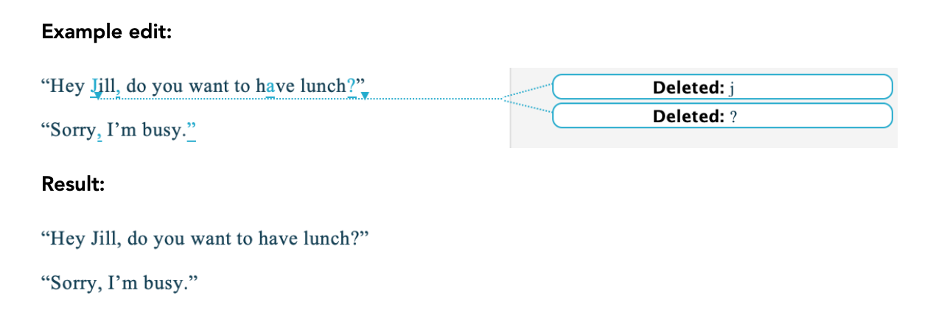

Here is how a proofreader might approach our sample lines:

Copyeditor

Other terms people sometimes use to mean the same thing: Line Editor

A copyeditor focuses on the content and flow of the writing itself. This kind of editor will point out places where you are using clichés, where the pacing slows, where the voice is inconsistent, where the meaning is vague, where it feels like something is missing, or there is a problem with logic or consistency. Sometimes people use the term “line editor” to refer to a copyeditor because they are working at the level of the line, sentence, or paragraph.

The kind of edit an editor at a publishing house is most likely to perform on your manuscript is a copyedit. It is usually done when the content of a manuscript is finished. When a manuscript is being copyedited at a publishing house, it is said to be in production, which means the writing phase is over. There will be a copyedit and then there will be a proofread to make sure that the work is technically accurate.

The key thing to know is that copyeditors generally work on a line-by-line basis. They assume that the big-picture elements of the work are in place and will probably not question the narrative design or structure of the work unless there is something egregiously wrong.

Can AI help with copyediting? Sure. AI can now point out a staggering number of issues with a piece of writing. It suggested that I change the sentence above — “The kind of edit an editor at a publishing house is most likely to perform on your manuscript is a copyedit.” It told me the sentence was passive and could be tightened up, which is true. But I decided to keep it because that sentence said exactly what I meant to say. All of this is to say that AI is useful, but not human.

Note that some copyeditors will also point out proofreading errors (and some proofreaders will point out issues a copyeditor might focus on) – but anytime you are making changes to a manuscript, there is the possibility of introducing mistakes, so a final proofread is always a good idea.

Developmental Editor

Other terms people sometimes use to mean the same thing: Structural editor; Substantive editor; Manuscript reviewer.

A developmental editor is thinking on a bigger scale than the line or paragraph. They are thinking about the impact of the book on the reader — the logic of it, the interior lives of the characters (in memoir and fiction), the world of the story (in fiction), the demands of the genre, and the flow and power of the argument (in nonfiction) – among other things. This is big picture editing, big idea editing, whole book editing.

A developmental editor usually does one round of edits on the pages, all at one time. They read the complete manuscript, make their comments and suggestions, and send it back to the writer. The writer goes off and makes the changes they wish to make, with the goal of making the work ready for a copyeditor and proofreader.

A good developmental editor will understand the genre conventions and will be up to date on industry standards on word counts.

Some editors at publishing houses will do a developmental edit with their writers, but in my experience, they are few and far between. Writers usually seek out developmental editors before they get to the publishing stage — when they are ready to take their work from good to great and know they can’t do it alone.

Note that some development editors will do more than one round of editorial review. In other words, they will review your revisions. If this is a process you think would be helpful, make sure your developmental editor will provide this kind of service. This practice gets closer to book coaching, which we will get to next.

Example Edit

Result

Book Coach

A book coach does the same work a developmental editor does, but with two important distinctions:

1. A book coach is often guiding the work and the project forward as it is being written (or rewritten.) Instead of waiting for a project to be complete, a book coach might be there from the beginning as the writer defines the project and their goals. The coach will also walk alongside the writer as they write forward, keeping them accountable and helping them stay on track. They provide deadlines and feedback as the writer moves forward chapter by chapter. A book coach is usually engaged with the project over a long period of time.

It is a matter of preference which process makes the most sense for each writer. Author Accelerator Book Coach and novelist Sheila Athens explains how she has experiences the difference:

“I’ve also used developmental editors in the past, meaning that I hired someone to provide feedback on the story after the entire manuscript was written. I got good feedback, but book coaching—getting feedback along the way—works better for me. I like the potential for course correction with each twenty-five page submission. I like the fact that if the story is going off the rails for whatever reason, I can get it back ON the rails because I’ve gotten that feedback along the way, rather than having to wait until the entire manuscript is written to have gotten that feedback.”

2. The second difference between a developmental editor and a book coach is that the book coach supports the writer not just from an editorial standpoint but from a project management and emotional standpoint, as well. In addition to helping the writer with their manuscript, they may help with career decisions, choosing a path to publishing, and deciding when a project is ready for pitching and publication. They may help with the ups and downs of the creative process, talking through a writer’s doubts and helping them through dry spells and rejection.

There tends to be a lot of back-and-forth between a writer and a book coach, and this builds a relationship around the work. It’s a relationship built on trust and a mutual dedication to helping the work become the best it can be.

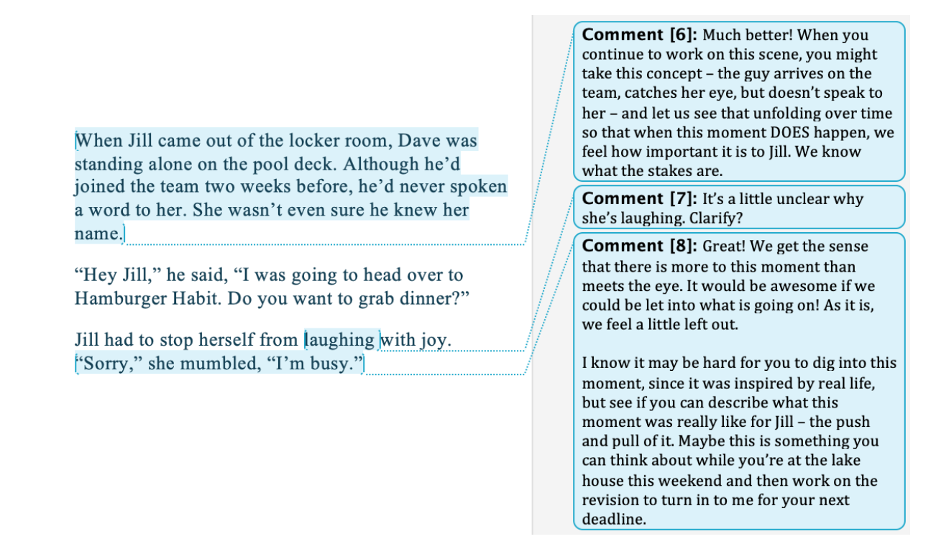

In our example, if a book coach saw the revised lines, above, they might have made comments like this:

Example Edit

When the book coach next saw those revised lines, they might make a comment like #9, below:

From these descriptions, you can see how important it is for a writer to ask for the right kind of help at the right time.

As a hard-working certified book coach, I'm grateful for this wonderfully accurate portrayal of the breadth-of-service that a book coach typically offers a writer--and for clearly setting the book coach apart from other essential kinds of editors. (By 'apart' I do NOT mean 'above,' simply that we don't all do precisely the same job.) Great job!

This is such a great demonstration of the different kinds of engagement with a manuscript... and it arrived just as I was puzzling out how to make the same explanation to a client. Amazing! Thank you for all you do!